NZ Gardener magazine, May 2023

Experts think they know why native kākā were attacking trees in Wellington

Bee Dawson

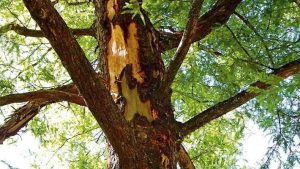

Kākā attacking a tree.

Up until the 19th century, the lively and beautiful kākā was common in the forests of Aotearoa, an integral part of a well-established, stable ecosystem.

This harmony disappeared following the advent of the first European settlers. When spotted with a wheelbarrow of freshly shot kākā in the 1870s, farmer Job Wilton was probably taking his avian booty into the city.

At this time, a visitor observed that in Wellington’s poulterer shops, “the curious parrot, or kākā, Nestor meridionalis, is hung up for sale.” Their feathers are also likely to have been in demand as fashion decorations for ladies’ mantles, muffs and fans.

However, it was the widespread destruction of the kākā’s forest habitat and the introduction of predatory pests that led to them becoming effectively extinct in the city by the early 20th century.

Dawn redwood with bark stripped by kākā.

All started to change some 16 years ago when the Zealandia Ecosanctuary in Karori reintroduced several breeding pairs. The kākā rapidly settled in and then bred so prolifically that the population increased 250% between 2011 and 2020. It’s been an outstanding conservation success story – for the birds.

But there has been an unexpected downside. As numbers built up and kākā spread around the city, they started to attack and kill exotic trees, including historic northern hemisphere conifers in the Wellington Botanic Garden.

A macrocarpa that was planted in 1875 and an 1895 sequoia were some of the first casualties. “That’s an unfortunate loss to botanical history,” David Sole, the manager of Wellington Gardens, says. “We’ll never know how long those trees would have lived.”

Our native kākā is an outstanding conservation success story – for the birds. This one was spotted by author Janet Hunt in New Plymouth in 2022.

The problem is so new that no-one really understands what is happening. One theory is that the birds are hunting for insects, but there probably aren’t enough of those to explain the extent of the devastation. Another theory is that the damage is caused by juvenile kākā clowning around.

The third, and currently most plausible, theory is that the kākā, which are one of the few sap feeders in the world, are mostly interested in accessing sweet tree sap. “This fits in with the systematic nature of what we’re seeing,” Sole notes. “The birds graze from tree to tree to tree, removing strips of bark, sometimes several metres long, as they go.”

These intelligent birds adapt their techniques according to their culinary target. When an Australian gum or a northern hemisphere deciduous tree takes their fancy, they attack the trunk in a circular “sewing machine” pattern. “They’re really getting stuck into Chinese elms at the moment,” says Sole. “There’s been significant damage to trees on Lambton Quay and in front of St Paul’s Cathedral.”

He notes that although kākā initially concentrated on redwoods, they have recently moved onto Norfolk pines. “A couple at the top of the gardens have been smashed. In another spot, one Norfolk pine is untouched (as yet) while its neighbour is under serious attack. Interestingly, their close relations, the bunya bunya and hoop pines, are perfectly okay. That may be because they’re Australian so have co-evolved with parrots.”

It’s also intriguing to note which trees are escaping what is widely described as a massacre. Sole points out that various pines (radiata, pinaster and muricata) planted in 1875 are largely unscathed; “Kākā have been seen having a nibble, but no more. The sap is probably too astringent.”

Pōhutukawa also seem free from attack. Other native trees such as tōtara sustain some damage but recover easily.

In terms of vulnerability, all conifers in the Wellington area are under threat, and redwoods especially so. Members of the Chamaecyparis family (this includes conifers such as the Lawson cypress), are seriously affected. Several macrocarpa in the Bolton St cemetery have been damaged; others are expected to follow. Eucalypts are a mixed bag: Some have been attacked but others are untouched.

Debarked branches are routinely cut off in an attempt to maximise the life of some trees, but many others have been, or will be, cut down as they die and become dangerous. This isn’t all bad – in some designated bush areas, kākā damage has sped up the planned removal of exotic species.

It’s telling that the Botanic Garden’s 30-year tree plan has now been brought back to a 10-year one. The main challenge is to change plants without compromising biodiversity. The Botanic Garden remains committed to a conifer framework, but using New Zealand native conifers such as rimu, tōtara, kahikatea, miro and matai rather than exotic species. Wherever possible, seeds are eco-sourced from the region. New Zealand conifers are all relatively slow growing, so replacement is a long-term challenge.

This is not just a Botanic Garden issue. Kākā have stripped trees all around Wellington and will continue to do so both in the city and further afield. Sole smiles wryly as he comments that kākā are now being reintroduced to Dunedin. “We are warning them!”

However, he also stresses: “Kākā aren’t the problem. People are the problem. European settlers brought the trees and the resurgent kākā population are now reaping the reward. It’s up to us to adapt.”

PHOTO: SUPPLIED / JANET HUNT/STUFF

Our native kākā is an outstanding conservation success story – for the birds. This one was spotted by author Janet Hunt in New Plymouth in 2022.

First published in NZ Gardener magazine’s May 2023 issue